He’s not wrong, yet everything about him is. Geneve watched Sight of Day work with Meriwether. The Feybrind coaxed the ferry horses to higher effort, while Meriwether worked the craft’s controls. She’d thought the vessel rudderless, but he explained it was merely mostly useless.

The ferry made slow yet steady progress to the far bank. The water swept them further with every moment, but she couldn’t work up the energy to be concerned. She was exhausted, and not just by the sinner’s prattle. Geneve had slept a little but worked harder. She’d worn full armor for days and felt ready for the knacker’s yard.

What really wore on her wasn’t physical ailments. The Tresward trained her to be their strong arm of justice in the world. To wear armor not to protect herself, but others. The weight she carried was something deeper and more personal. It revolved around a single question.

Why did the Justiciar save Israel and Vertiline, but not me?

It was a selfish thought, but one she needed to put to rest. She replayed the temple battle in her mind over and over. She saw the Valiant and Chevalier step through the glowing portal, then watched it snap shut. It left her and the sinner trapped with the Vhemin. Vhemin who wanted the sinner for the knowledge he carried.

Two things felt true. First, the Vhemin were part of someone’s plan, and second, her loss was a convenient accidental victory for said someone.

Her brain felt sluggish, unused to this kind of work. Geneve was trained to see things as they were, but she had no special skills in politics. The work of words was given to Clerics, not Knights. Despite that, with the water lulling her body to rest and her mind to peace, she set her thoughts free. Adrift like the ferry, she thought of who stood to gain.

Demons were the obvious culprits, but proving their continued existence was as tenuous as the Ledger of Lost Souls. Demons were a catch-all. They would curdle milk, or cause cows to miscarry. If you found a dead bird in your house, demons must have done it. The Tresward trained Knights to face demons, but only because history claimed they’d faced them eight hundred years before when the world broke. The demons fell, and in eight hundred years no one had seen them again.

So, unlikely then.

The sinner’s words nagged at her. You haven’t always hunted sinners. What had he meant? To cause her to doubt her purpose? Idle speculation? It was hard to know the mind of evil.

Geneve glanced at the man. He worked with the Feybrind, sharing a laugh as the horses picked up speed, the bank drawing closer. He wore no shirt, just a bandage, and it let her see the ruin hands of men made of his flesh. She’d seen scars on this front, but his back was a lattice of deep lash marks. He was undernourished, and if she’d found him beside the road with a beggar’s bowl she’d not have looked twice.

He isn’t evil. Save me, Three, but he isn’t evil. He knows its shape and weight. He’s felt its hand, sure as the dawn will come tomorrow. But it’s not inside him. She felt the heft of the thought and knew it for a deeper truth than the Tresward’s teaching. Something inside her worried at the problem, because it meant one other thing was true.

Meriwether isn’t a sinner. We’ve hunted his kind for a hundred years, but not hundreds, as he said. Like a puzzle box, something clicked in her mind, and Geneve felt she had it. She stood, muscles protesting, the sullen passive ache of overuse worrying at her. “Hah!” Meriwether turned to face her. The smile fell from his face, and it cut her. I’ve done that to him. Made him fear the Tresward’s Light. “Israel taught me a truth.”

“A truth, huh?” Meriwether looked doubtful, as if anything that came from a hulking Valiant could be wisdom.

“Aye. You can torture a man, but you’ll get whatever he thinks you want to hear. Bargain with him, and you’ll get what can be bought. Gamble with reprobates, and you’ll tar your fingers with dirty nothings.” Geneve arched her back, feeling her spine pop.

“That sounds like the kind of nonsense a Tresward-going sort might say.”

{He’s not wrong. Sounds like sermonizing.}

“Hush, you.” She shook her head, her own half-smile forming, unsure of who she was talking to. “He told me the only way you can be sure of hearing truth is from those with nothing to lose.” Water lapped the ferry. Tristan shifted, his big head nosing her. All else was still and quiet. “Meriwether, you spoke truth to power because you’d lost everything already. I treasure the gift.”

“Uh, sure.”

“We will find the conclave Sight of Day speaks of.”

“That’s good news.” Meriwether brightened. “I mean, it’s great—”

“When we find them, we will find more truth. They have nothing to lose, except their lives.” She crossed her arms.

Sight of Day glanced at Meriwether, who glanced right back. “Great speech, but maybe I should do the talking when we get there.” His brow furrowed in concentration. “You’re not using this as a trick to get close to a bunch of sinners and kill ‘em all?”

“I might be.” She shrugged. “You’ll need to trust me.”

“Hah! Oh, you’re not joking.”

“The thing is, sin… Meriwether,” she forced his name over the top of her train of thought, “there are many things that aren’t right. The first thing is the Justiciar left you with the Vhemin. The second is he left me, too. This means—”

“You’re a scapegoat.” The young man nodded.

She raised an eyebrow. “I am?”

{You are, but unfortunately for this Justiciar, a very angry goat.} Sight of Day offered a half-smile. {This isn’t a bad thing.}

She sighed. “The hidden truth you don’t see is this: the Justiciar is in league with the Vhemin. I have seen Clerics work a thousand times. They can turn the sky blue at night, or a person love another. The Divine Sway lets those closest to the Light work miracles in the Three’s name. Ambrose could’ve turned their bodies to ash or made them see fairy dust and moonbeams while we escaped.”

“You suspect corruption?”

“I suspect I don’t have all the information, so we’ll find the conclave and get it from them, by word or steel.” She offered Meriwether a small, tired smile. “It means another thing. I still need to keep you alive, for a while at least.”

“Excellent. Wait. What do you mean, ‘for a while?’ What happens then?” He rubbed the back of his neck.

“Truth.” She scanned the bank. It was very close. They’d be ashore soon. “They will send Knights after me. If we’re very lucky, it won’t be Israel and Vertiline. A different three would be best.”

“Wouldn’t Israel be more lucky?” Meriwether began readying the horses, dodging Troubles’ attempt to bite him. “I mean, you know him. We could work something out.”

“Israel is incorruptible.” She gave a small shrug. “If he means to find and kill us, then we’ll be found and killed.”

{Sounds bad. Luckily, you have a Feybrind who is very good at not being found.}

Geneve thought about that for a while. She wondered at the High Priest’s ability to render the Feybrind senseless, murdering their village. “We need to get a defense against their power over you.”

“I thought the same thing.” Meriwether walked a circle around Sight of Day, who endured the scrutiny by simply ignoring it. “Aren’t Feybrind supposed to ignore magic tricks?”

{There is a not-magic that can bind us.} Sight of Day looked at his feet, tail lashing once. {They know my name.}

“What’s he saying?”

Geneve rubbed her face. “He’s not making a lot of sense. It’s been a day for it. Let’s get off this ferry, set its horses free, and find out where in the world we are.”

* * *

Where are we? wasn’t an easy question to answer. Geneve’s reckoning said they flowed downriver fifty klicks, perhaps more. But her knowledge of this area was sparse to the point of being threadbare. First order of business was finding a settlement.

They tried letting the ferry horses free, but the beasts followed them. Geneve figured it a sign and let them come with. They would find a home for them ahead. The odds of the ferry master being alive were slim, so returning them to home was not just impractical due to distance, but because there’d be no one to hand them over to. Meri named them Casket and Britches. They were a matched pair of black geldings, and when she’d asked which was Casket or Britches, he’d shrugged in a way that suggested he probably couldn’t tell them apart, but might, depending on which was more annoying.

Geneve let Sight of Day lead. The Feybrind took them through the scrub and trees that shouldered the river, finding a slender mud-slicked rut that might be, in a certain light, a road.

It looked like a storm was coming. Night marched toward them on faster feet with cloud to cover its approach. Meriwether stole a shirt from a scarecrow they passed. It was ripped in places, and smelled of straw, which she found funny, and he didn’t seem to.

She spied the village by the thin spindles of smoke in the air, almost lost against the dark gray cloudscape. They made the town’s verge as the light left almost entirely. The place was too small for a convenient signpost to mark its name, and well below the size that warranted lamps. She took over the lead, heading toward a larger low-slung building that had the look of an inn.

The front sported a trough for horses. A shady-looking lean-to on the right looked like something the overly optimistic would call a stables. Meriwether pulled his shirt close. “How you want to play this?”

“Play?”

{Play?}

“Yeah. We go inside, we’ve got a Knight, a cat, and—”

“Feybrind.”

“One of those too. Inside, he’ll draw attention. I think the easiest option is to call me your prisoner.” He rubbed his ear. “It’ll work.”

“It’ll be a lie.” She stamped to the steps.

“All things are, at some level.” Meriwether eyed the sky as a few drops of rain fell. “Fine. Not a prisoner, then. Leave it to me.” He breezed inside.

{We’re doomed.} Sight of Day followed the young man inside.

Geneve sighed. It felt like the sky rested on her shoulders. Pressing the door open, she was greeted with silence, woodsmoke, and the scent of cooking meat. A sour tang floated beneath it, almost like vinegar or spoiled vegetables. A portly man stood behind a sad-looking bar, the surface worn and stained. A collection of locals sat strewn about a common room, rude benches the only thing on offer.

“Hello,” Meriwether said. “I’m Lord Meriwether du Reeves. Apologies for my dress. I was set upon by villains, and this fine Knight,” he pointed to Geneve, “rescued me. We’re en route to the capital.” He offered a brilliant smile. “Would you have rooms?”

Geneve gawped. It was like a different man stood before her. Outside, Meriwether wore torn pants and a scarecrow’s shirt. Now he was dressed in a silk doublet and fine purple pants. His boots gleamed, reflecting the fire’s meager light. But it wasn’t his attire that drew the eye. His posture changed. Meri’s shoulders were straight, his head high. He almost looked down his nose at everyone. If she hadn’t shared the road with him for days, Geneve would have sworn he was, in point of fact, the Lord du Reeves.

The innkeeper, also in a state of astonishment, bobbed his head. “Aye, you’re lordship. Got a room. Not a good room. Bit small, to be honest.” The man held a tankard and stained rag, moving the rag to mop his forehead before returning to polishing the tankard. “Not really up to hosting folk of your quality here.”

“Think nothing of it,” Meriwether insisted. “Tonight, you are all my friends. Why? Because the du Reeves house still has its heir, and he is happy!” The young man clapped his hands. “A round for the house.” He scattered copper barons before the innkeeper. “Would you have a boy to tend the horses?”

The innkeeper gave a slow nod, remembered himself, and turned to the back, bawling, “Ollie! Get out here.” He gave a gap-toothed smile to Meriwether. “Apologies, m’lord. The boy’s a bit simple. Doesn’t hear too well, neither, since the horse kicked him in the head.”

Meriwether leaned forward. “And yet you do him the kindness of offering him work. Many in your stead would have turned him out, or sold him. You, sir, are a good man.”

“As you say, m’lord.” The innkeeper bustled toward the back, sliding across a dirty leather drape. Geneve glimpsed an even dirtier kitchen, and a positively filthy boy within, before the leather fell back, obscuring all.

She sidled to Meri’s side, leaving an astonished Sight of Day staring by the door. “Lord du Reeves?”

“The one and only.” He smoothed his silk shirt. “I’d recommend eating nothing but salted meat. This place doesn’t look clean.”

Geneve opened then closed her mouth. I feel stupid and slow. “But, du Reeves.”

“Aye.” He nodded, encouraging. “What of it?”

“The du Reeves barony is real.”

“The beauty of it is that it’s also hundreds of klicks north.” He broke out another fresh smile as the innkeeper returned. The man carried a small keg over one shoulder, setting it on the bar. “Ah. All’s well, I trust?”

“Aye, m’lord. You offered a round to everyone, is all.”

“That I did. And I wouldn’t mind one myself, hey?” Meri winked.

“No, m’lord. I mean, of course, m’lord, but not this swill.” The innkeeper beamed. “Got a bottle all the way from Tebrani. They say the wine’s as tasty as the lips of their maidens.” He looked too Geneve. “Beggin’ your pardon.”

Geneve felt like the world had turned upside down. She’d never seen anything like this. “Pardon given, of course.” She gave a sickly smile. “Do you have food?”

* * *

Dinner was greasy might-be-chicken suspended in might-be-broth. A few lonely carrots did laps about the bowl. It wasn’t the salted meat Meri recommended, but Geneve was too tired and hungry to care. Her companions sat opposite her, a stained wooden table between them. There wasn’t privacy in such a place. It was small, designed for locals who knew each other well enough to not mind sharing lice. Despite that, the locals previously at their table found places to be. Geneve imaged that might be her as much as the Feybrind. Knights had a reputation for murder, and folklore said Feybrind were all witches.

I don’t know about them being witches, but they are marvelous. More appealing than the locals, for certainty. Earning a little space through fear didn’t hurt at all, and she was too tired to talk with random people who were like as not inbred and superstitious to boot. She ate without lifting her face from her bowl and ordered a second helping from the innkeeper who’s love of coin overcame his fear of Knights and Feybrind. As the man ladled might-be-chicken into a ‘fresh’ bowl within the filthy kitchen, she had a moment to watch her companions. Meriwether stared into a wooden cup, a kind of sick fascination on his face. He’d managed to finish his might-be-broth but didn’t look up for a second round. Sight of Day was poking a spoon into the broth mixture, eyes narrowed.

“Something wrong?”

{Many things.} The Feybrind put down his spoon. {Top of mind for me is I wasn’t aware even humans could make food this bad. Also, I can’t eat carrots.}

Meriwether watched Sight of Day’s handspeak without comment. “Try the carrots, they’re not half bad.” Geneve’s second bowl arrived. She thanked the innkeeper with a nod and bent to her task of emptying it. After five mouthfuls, she felt eyes on her. Raising her head, she saw both Meri and Sight of Day staring at her. Meriwether swirled his cup of ‘Tebrani red,’ not looking interested in a second taste. “Try breathing this time.”

Geneve jabbed her spoon at him. “Try not breathing.”

Sight of Day rolled his golden eyes. {While you’re eating, spare some thought for our next steps. We need to head north.}

“What’s north?” Geneve wiped her chin.

“Fashion, good food, and doxies without disease.” Meriwether shrugged as she raised an eyebrow. “It’s easier to not worry about what the cat said and try to invent my own conversational fun.”

{The north holds the capital of the human kingdom Ors’en. Queen Morgan is friend of the People.}

Geneve put her spoon on the table. “What kind of friend?”

Golden eyes considered her. {The kind that offers friendship.}

Geneve’s brow furrowed. Meriwether watched her. “He being oblique again?”

She grunted, retrieving her spoon. “He’s being Feybrind. It’s kind of how they are.”

{We are excellent conversationalists.} A small half-smile accompanied Sight of Day’s handspeak. {We are also used to using small words when dealing with your kind. It’s nothing personal.}

Geneve snorted. “We can’t go north. There’s a huge desert in the way. The desert is a wasteland of terrors. The Clerics talk of sand that can swallow a person whole in seconds. Parts of it hold relics of the old world, from when the ancients scorched the earth. We don’t go there.”

Meriwether took a sip of his wine, and his face told a story of many regrets. Lips puckered, he managed, “I thought you didn’t get disease?”

“Our horses die from it easy enough, and in a sun-baked, waterless land, we die of thirst like everyone else.” Her might-be-chicken didn’t taste so good anymore. “We go north and west, or north and east.”

“It’ll take weeks.”

“It will. It’s how we got here in the first place.”

{You mentioned monsters. You mean the Vhemin?}

Geneve shook her head. “Partly. The Vhemin live there. It’s hot and dry. I don’t know how they survive the blasted ground, but it’s their home. I’m more thinking of the beasts said to roam the wastes.” Requiem leaned against the table’s end, and she glanced at the worn pommel. “When dragons flew the skies, they roosted in the desert. Stories say they also liked it hot.”

“There aren’t any dragons left.” Meriwether laughed, a slightly pitying sound as if he’d heard a small child claim the sky was black during the day.

“The Tresward keeps records—”

“If there were giant, carnivorous flying monsters, they wouldn’t hang about in a shitty desert, content with table scraps. They’d have knocked us right to the bottom of the food chain. Hell, there’d be one roosting in this town, because of all the slow-moving, stupid people.”

The innkeeper chose that moment to arrive, cutting off conversation Geneve felt should best be kept quiet. The man wiped dirty hands on his dirtier apron, the movement obsequious. Close up, he didn’t smell very fresh, and Geneve could see dirt seamed into the wrinkles of his hands and face. “Beggin’ your pardons, but how’s the food? The wine?”

“Excellent.” Meriwether put his cup on the table. “So good, in fact, it seems a crime to horde it to myself. Perhaps share it among your regulars?”

The innkeeper looked aghast. “It’s Tebrani red, m’lord.”

“Ah.” Meriwether’s smile became fixed, like a seized cart axel. “I find myself in a good mood. It’s being alive that does it, after facing certain death. It’s like I’ve had the best theater show in the world, delivered right,” he tapped his chest, “to my heart.”

“If it’s theaters you’re after, you should stay for the execution.” The innkeeper glanced to the bar, where his boy Ollie stood like a small post. “Bound to be excitement at an event like that. I’ll be selling fresh sausages in hot bread.”

Sight of Day pushed his bowl away. {I find myself less hungry.}

{Wait.} Geneve held her palm out to the Feybrind. “Execution?”

“Aye. We caught one of the monsters that razed Old Pencer’s farm. Killed his wife, kids, and best cow.”

“What monster?” Geneve half-rose. “Where is it?”

“In the lock-up.” The innkeeper retreated a step as she shoved her bench back. “We caught a Vhemin.”

If you enjoyed this, consider supporting me on Ko-Fi or hopping on my mailing list.

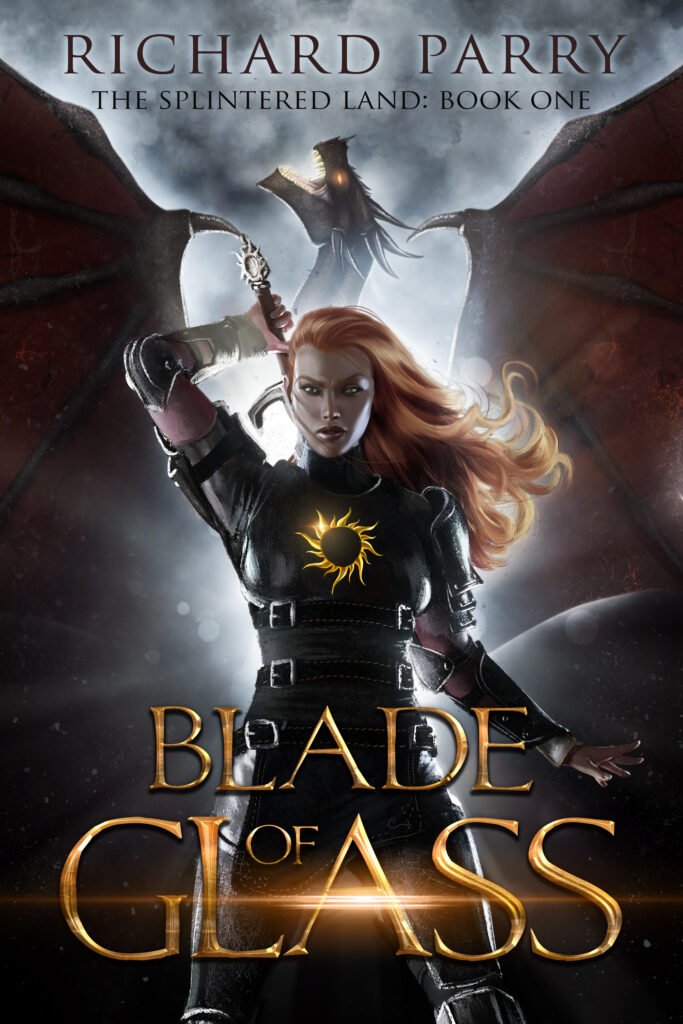

Miss the other parts of Blade of Glass?

[First Chapter] | [Previous Chapter] | [Next Chapter] (Live 10 September 2024)

Discover more from Parrydox

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.