I’ve been shot before, but this time the assholes didn’t have the courtesy to aim. Hitting me was accidental, and that hurts almost more than the barb. Meriwether felt the world came to him through flashes of too-bright light and too-muted sound. The only real thing was the pain in his chest, a deep, grating, personal fire that made everything else seem less important. In any other situation he’d marvel at Geneve’s sweeping shield work as the Knight danced across the ferry’s deck. Her red hair flew as she spun, and maybe it was the delirium setting in, but he thought she did it with her eyes closed.

Closed, for pity’s sake.

Light glinted from the water. It felt like the blinding brilliance of the Three come for him at last. He felt the certainty of it, the hungering justice of angry gods wanting his end. They sent Vhemin to find me. “I’m going to die,” he croaked.

Sight of Day crouched beside him. The Feybrind shook his head, putting a soft hand on Meriwether’s shoulder. The meaning was clear. Stay still. We’ve got this. Then, like the implacable toppling of a burning building, the Feybrind slumped to the deck.

Meriwether looked to Geneve, but she was lost in one of the four, sixteen, seven hundred, or whatever-it-was battle steps of gods who wanted sinners dead. The Feybrind was down, but not out. His golden eyes stared at the sky, seeing nothing. Meriwether groaned, rolling himself onto his side. The pain as the bolt in his shoulder worried at his clavicle was exquisite and pure, and he needed a minute to steady himself. Nausea rose, but he stemmed the tide with a single thought: if I puke on the cat, I’ll never live it down.

He waved a hand over Sight of Day’s eyes. Nothing. Not even the twitch of an eyelid. His body was unharmed as near as Meriwether could see. No crossbow bolts sprouted from his fur, although it felt a disservice to the Knight’s efforts to bother checking. Her dance was perfect. He almost got lost watching her for a moment, then the ferry listed, his elbow slipped on the decking, and his injury screamed blue murder inside him.

Right. Got the message. Do something useful. Meriwether looked past the sweeping grace of Geneve to the Vhemin on the bank. There, sure as Knights came for sinners, was the High Priest himself. The scaled monster grinned a grisly smile. His skin had the dark not-glow it had back in the underground temple. Meriwether looked to Sight of Day, then the priest. They’ve got a trick to unwind the cats. That’s how they took over an entire village. It feels like cheating.

“Geneve,” he rasped. She didn’t seem to hear him, so he gathered a little strength, mere fragments really, and put it into his next words. “I need your scattergun.”

That made her stop. Her hair settled about her face. She was sweating, breastplate rising and falling as she breathed hard and strong. “I need another two Knights, but wishing won’t make it so.”

“Just … trust me,” he urged. “It’s for the cat.”

She looked to the prone Sight of Day, then swatted a crossbow bolt from the air almost casually with the rim of her shield. The bolt shattered into fragments that rattled across the deck before slipping into the water. Geneve didn’t do anything stupid like demand answers for what happened to the cat. She unslung her scattergun, cracked it open, and extracted a paper tube. Snapping it closed, she handed it to him. “One shot, sinner. Make it count.”

He heard the challenge in her tone. Meriwether heard try it nestled in there somewhere. He let out a groan—couldn’t help it, really, what with his lifeblood leaking all over the old wood deck of a ferry, pain in his shoulder so intense it felt like someone pushed the glowing tip of a brand against his flesh and left it there. Poison, he realized. The fuckers poison their weapons.

The ferry’s timbers groaned and creaked beneath him. The vessel’s motion shifted, edging back toward the Vhemin’s side of the river.

“No one fights fair,” he hissed, laying across the Feybrind. He leveled the scattergun across the water, lining up the High Priest. He pulled the trigger.

The weapon roared, a plume of white-gray smoke blasting from its mouth. A circular chunk of the ferry’s deck vanished into splinters as the scattergun chewed on it. The High Priest ducked aside, a pointless exercise at this range, but Meriwether expected it. Intellectually a man might know the range of a weapon, but emotionally he’d still want to be out of the way just in case, right? Especially since there was no sure way of knowing what Tresward weapons could do, regardless of the range. The priest’s black-tinged aura vanished.

Sight of Day gasped, sitting bolt upright. The movement knocked Meriwether aside, and he screamed in pain, dropping the scattergun. It slid toward the side of the ferry, but the Feybrind’s hand darted out cat-swift, snaring it. He tossed it to Geneve and stood in a fluid motion, making both actions look like one.

Meriwether gave him a small wave, then slipped into blackness. It seemed the best place to be.

* * *

When he woke, the sky was darker, marching toward dusk. The ferry still charted its course downriver, which was now significantly wider than it’d been before, but that was the way of rivers. Geneve rested in the shade of the ferry’s meager cabin. Sight of Day prowled the deck. The horses looked unconcerned about pretty much everything, eying the banks and no doubt wishing for clover.

Meriwether touched his chest. The bolt was gone, a clean bandage hiding the wound. Where his fingers probed, he felt pain, but not fire. “Thanks.”

Geneve’s eyes slid in his direction. The dimming light made them the color of green actinolite. “Sight of Day pulled it while you were out. He said it was poisoned.”

“I figured. But not with something lethal, right? Otherwise I’d be dead.”

“Otherwise,” she agreed. “I’m beginning to think the Vhemin want something with you.”

“I’m beginning to think you didn’t go to Tresward school or whatever you call it just to eat your lunch.” He hissed as his fingers brushed a more sensitive part of his injury.

Sight of Day’s fingers flicked in his rapid handspeak, and Geneve laughed. “He says to stop playing with it.”

“What else did he say?” Meriwether’s suspicion was high because of the cat’s half-smile.

“It was the way he said it.” She looked at the far bank. “I think this voyage is cursed. We haven’t hit the bank yet. The odds of that happening soon seem unlikely.”

“Oh, that.” Meriwether moved to a sitting position with a heartfelt groan. “It’s because we are cursed. The High Priest,” he waved a hand upriver, “worked his magic. Knocked out the cat, and I think was trying to lasso us to the bank.”

Geneve stood, looking in the direction he pointed, then to the bank. “They can do that?”

“They’re doing a lot of things they’re not known for.” He eased himself to his feet, feeling about a hundred years old. “Hot rocks. Massive incursions into the south lands. Burning villages.” Meriwether looked to Sight of Day, then at his feet. “I’m … so very sorry.” He felt the Feybrind approach and dared a look into those golden eyes. There was sadness there as the cat laid a gentle hand on his shoulder. Meriwether clasped the Feybrind’s hand. “There are no words. I want time to sit with you. When we get to a village, we’ll drink, and tell stories. The world should hear them.”

He felt Geneve’s eyes on him, so let his arm drop. “What do they want, sinner? What could they want from you?”

Meriwether sighed. “I’ve been wondering the same thing. No,” he raised a hand in supplication, “this isn’t a joke. I really don’t know. But I figure someone does.” He jabbed a finger at Sight of Day. “Him.”

Geneve looked between the two of them. “The Feybrind?”

Sight of Day watched Meriwether for a moment. He offered an apologetic shrug in Geneve’s direction, his hands moving. Meriwether frowned. “What’d he say?”

“The oddest thing.” Geneve strode forward. “He said he can’t tell me.”

“Us, you mean.”

“Did I stutter?” She shook her head, red hair lashing her face. “He says there’s a secret inside you. It is the key to the Tresward and the kingdom.”

Meriwether rubbed his chin, feeling the rasp of unruly stubble. “Lots of secrets in me, I’ll agree. They keep me alive.” He eyed the cat. “What kind of secret’s so secret even I don’t know it? I think I’d know a secret that links Tresward and kingdom.”

Geneve touched Meriwether’s arm. Just the hint of fingers, then they were gone. “I think I want to know a secret that’s cost me two Knights and a world of suffering.”

“Not like that,” suggested Meriwether.

“Like what?”

“You’ve got one speed. It’s all, bash this, pummel that. It’s awe-inspiring, but not the right tool for the job.” Ignoring her incredulous look, he focused his attention on Sight of Day. The cat’s left ear flicked but otherwise he made no move. “I think you want to tell us the secret your entire village died for. I think your people scream for peace, but the secret holds their souls to the ground. It’s like an anchor, chaining them to this world. Or a sickness, I don’t know. But I see it in your eyes. No,” he touched the Feybrind’s chin as the cat made to look away, “please. Listen. If I can help, I will. I just need to know how.”

Sight of Day sagged a little, then his hands moved. As Geneve translated, Meriwether kept his eyes on the cat. “He says they want the Ledger of Lost Souls.”

“Great. What’s that?”

She snorted, drawing his eye. “You don’t know?”

“I’m a sinner, not a scholar. I have no idea whose souls they are or how they got lost. Break it down for me.” Meriwether raised an eyebrow.

She scratched her head, ruffling her hair. “It’s a myth.” The Feybrind’s hands moved. “It is a myth! A fairy story.” Geneve held up her hand to forestall Sight of Day’s words. “Okay, okay. It’s a book.”

“Hence the term ‘ledger,’” Meriwether said.

Geneve scowled. “Do you want to tell the story?”

“I wish I could.”

She growled. “The Ledger of Lost Souls is a mythical,” Geneve leaned on the word, “tome collecting the names of Tresward Knights doomed to die. It’s a record of all of us stretching back in time and reaching forward to the future.” She crossed her arms with a creak of armor. “It’s said that writing a Knight’s name in it will end their life.”

“Oh, is that all?” At Geneve’s blink, Meriwether smiled. “I’ve seen it.”

“The Ledger of Lost Souls?” She glanced to Sight of Day, then back to him, before breaking into a hearty laugh. She braced hands on hips, head thrown back, cackling at the sky.

Meriwether pursed his lips, glancing at the cat, who shrugged, finger circling his temple, as if to say humans are crazy. “I mean, I’m not sure I’ve seen it, but I’m pretty sure I have. In Calterburry, where you found me. I was investigating a house—”

“Robbing it, you mean.”

“If you like. Big place, lots of locks, for all the good they did. I found a library.” Meriwether paused, glancing at the sky. “Some of the books were so old the dust made me sneeze. I’m pretty sure that’s how they caught me.”

“You were brought low by a sneeze?”

“Or the tremendous number of guards. Hard to say.” Meriwether scratched his bandage, wincing at the pain. “It itches.”

“Don’t change the subject.” She leaned closer. He smelled her armor, and that elusive just-Geneve scent. He thought he liked it, quite a lot. “You’ve seen the Ledger? The book that, should you write a Knight’s name in it, they’ll die?”

“Sure, why not?” Meriwether frowned. “Seems a handy thing for your enemies to have. You should go get it.”

Sight of Day’s hands swept the air, sure and certain, almost urgent. “He says they need to see it to destroy it. Wait. Who’s ‘they?’” Geneve took a step closer to Sight of Day, eyes narrowed. “Better question. You were looking for us?”

“That’s obvious. I’ve got an idea! Why don’t we let him tell the story from the start, without interruptions?” Meriwether faced Geneve’s scowl with a bravery only skin deep. “Here’s the thing, Red—”

“Red?” Her voice rose an octave.

“The thing is, he knows what’s going on and we don’t. Maybe not the whole of the thing, as I’ll wager the Vhemin weren’t part of the plan. He probably thought he’d find three Knights, and spirit me away at night.”

“Under full guard?”

“Looks quiet on his feet,” Meriwether mused. “Bet he could’ve slipped you some angel’s kiss if I hadn’t.”

Sight of Day took one look at Geneve’s face, then shook his head, the motion sharp and hard. His hands moved, and she translated. “There is a conclave of sinners. With a seeming of the book, they can transport it to a location. At this place they can destroy it, ending the tyranny against the Tresward.” She frowned. “What tyranny?”

“There aren’t a lot of you, are there?” Meriwether tapped his chin. “I’ve seen you fight. Israel and Vertiline, too. A force like that seems impossible to beat.”

“The training—”

“Come on,” Meriwether insisted. He thought about tapping her in the middle of the forehead, almost made the movement, but knew he’d end up on his back, probably with his arm broken. “Use your head, Knight. A bunch of assholes in Calterburry wanted to take my magic away. What if they really wanted to take the Ledger away? Stop the knowledge getting to this conclave?”

“That can’t be it.” Geneve’s brow furrowed in confusion.

“It can, but the news is bad for one of us at least. See, if the cat’s right—”

“He’s a Feybrind.”

“If Sight of Day’s right, you need me unjudged… is that a word? You need me alive, and at the conclave, to gin up the book for them. But it gets worse.”

She sank to her haunches. “It gets worse?” Her voice was faint.

“It does. Because the only way this gets fixed is with more sin. The conclave? I bet it’s a collection of wizards, witches, and other unsavory sorts. A whole posse of sinners.” He crossed his arms in satisfaction, the motion somewhat marred by his sharp intake of breath as he pulled his injury. “A conclave sounds like more than a couple people. It sounds like a horde. Sorcerers of old.” He paused, thinking. “Oh.”

“What else could be wrong?” She stared up at him, and for a moment his heart went out to her. She looked adrift, rudderless like their ferry.

“Something really, really bad must be going on if the conclave wants to help the Tresward. You guys are doing all the killing of the other.” He tapped his chin. “Unless it’s a lie, and they want the Ledger to write more names in it.”

Geneve looked at her hands. They lay curled in her lap, empty of weapon and purpose. “There are too many things here that don’t make sense.”

“Yep,” Meriwether agreed. “One of the biggest ones is, why are we still traveling down this river?”

“The curse. You said it yourself.”

“Not great for teaching lateral thinking, these Tresward schools.” Meriwether pointed to the ferry’s horses. “Let’s get these guys working.”

If you enjoyed this, consider supporting me on Ko-Fi or hopping on my mailing list.

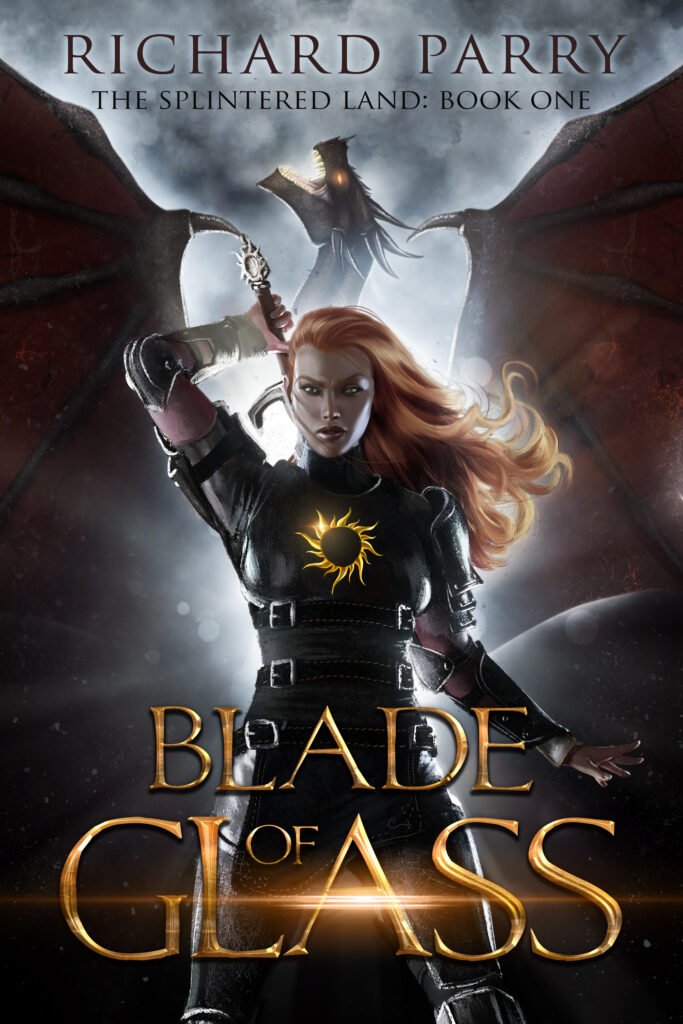

Miss the other parts of Blade of Glass?

[First Chapter] | [Previous Chapter] | [Next Chapter] (Live 5 September 2024)

Discover more from Parrydox

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.